Artículo de Investigación

Differences Between Sexes in Psychopathological Variables among Adolescent Victims of Dating Violence

Diferencias por Sexo en Variables Psicopatológicas entre Adolescentes Víctimas de Violencia en el Noviazgo

César Armando Rey Anacona

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9528-2199

Jorge Arturo Martínez Gómez

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1423-3812

Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia; Clinical and Health Psychology Research Group.

Correspondencia: cesar.rey@uptc.edu.co

Abstract

This descriptive-comparative study had the aim of examining if there were differences between sexes with respect to a number of psychopathological variables and other issues among adolescents who are victims of dating violence. There were 757 participants, adolescents between 12 and 19 years of age; 59% were female (and 41% male), from 15 different secondary education institutions in two intermediate-sized cities in Colombia. The following instruments were used: the Spanish version of Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI), the Behavior Assessment System for Children and Adolescents -self-report version- (BASC-S3), the Symptoms Checklist SCL-90-R and a self-report, psychological variable questionnaire. The boys surveyed reported having received more relational and physical aggression. However, the girls demonstrated a significantly higher frequency in terms of psychopathological symptoms, more severe clinical and personal maladjustment, and bad relationships with peers and relatives. This indicates that the girls who are victims of these forms of violence suffer more difficulties, an aspect that should be taken into consideration in the prevention and intervention campaigns related with this issue.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, dating, adolescents, differences by sex, mental health.

Resumen

Este estudio descriptivo comparativo tuvo como objetivo examinar si existían diferencias por sexo con respecto a un conjunto de variables psicopatológicas y otras dificultades, entre adolescentes víctimas de violencia en el noviazgo (VN). Participaron 757 adolescentes entre 12 y 19 años de edad, el 59% mujeres, vinculados a 15 instituciones de educación media de dos ciudades intermedias de Colombia. Se utilizó la versión española del Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI), el Sistema de Evaluación de la Conducta de Niños y Adolescentes -versión de auto informe- (BASC-S3), la Lista de Síntomas SCL-90-R y un cuestionario de auto-informe de variables psicológicas. Los varones reportaron haber recibido una frecuencia mayor de malos tratos de tipo relacfonal y físico. Sin embargo, las mujeres evidenciaron una frecuencia significativamente mayor de síntomas psicopatológicos, un mayor desajuste clínico y personal, y malas relacfones con pares y familiares, lo cual indica que las mujeres víctimas de esta forma de violencia presentan más dificultades, aspecto que debería ser considerado en las campañas prevención e intervención de esta problemática.

Palabras clave: Valencia de pareja, noviazgo, adolescentes, diferencias por sexo, salud mental.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period of preparation for adult life in which the individual must face a series of experiences in which the influence of peers is fundamental, such as the transition towards social and economic independence, the development of identity and first affective and sexual relationships, experiences that may pose risks to their physical and mental health, affecting their adaptation to their family, school and social environment (World Health Organization, 2017). Dating violence refers to all conduct which causes harm or discomfort at a physical, psychological or sexual level, in unmarried couples or couples who do not cohabit, generally adolescents or young adults (Rubio-Garay, López-González, Carrasco & Amor, 2017). The high prevalence rates of this form of violence have led it to be considered a public health issue (Ludin, Bottiani, Debnam, Solis & Bradshaw, 2018; Mercy & Tharp, 2015; Peterson et al., 2018; Sánchez-Jiménez, Muñoz-Fernández & Ortega-Rivera, 2018; Wilson et al., 2019; Wincentak, Connolly & Card, 2017).

An aspect that is not widely studied is connected to the differences between the sexes, regarding the difficulties associated with dating violence throughout adolescence. In females, anxiety, mood changes, and eating disorders are more common, which tend to begin at that stage in life. Among males, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and ADHD are more common, which tend to begin in childhood, in addition to disorders which develop due to substance abuse, which usually start in adolescence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In general, among males, externalizing problems are more common, that is to say, those which affect the people who surround the individual, such as aggressiveness, disobedience, destruction, and hyperactivity. Among females, problems of an internal nature are more common, which means those which affect the individual directly, such as anxiety, depression, isolation, fear and somatization (Alarcón & Bárrig, 2015; Carragher et al., 2016; Sluis et al., 2017). The aforementioned differences could be the result of cultural factors, such as gender expectations, and biological factors, like temperament and neurodevelopment (Sluis et al., 2017). Many of these difficulties appear or intensify in adolescence, given the typical tensions of this age and psychosocial circumstances, such as conflict in couples and bullying, and therefore it is unsurprising that they are also triggered by dating violence.

The few studies on differences by sex with regard to the difficulties presented in victims of dating violence point out that said difficulties tend to be greater among women than among men (Reed, Tolman & Ward, 2017; Rubio-Garay et al., 2015). A systematic review was carried out by Johnson et al. (2017) based on five studies that met the selection criteria and it was found that the risk of consuming marihuana is 54% among adolescents and young adults who are victims of physical dating violence, with the risk being greater for women. At the same time, a longitudinal study conducted by Foshee et al. (2013), with 3328 American students from grades eight to twelve found that, among the girls, having suffered psychological violence predicted the presence of internalizing symptoms while physical violence predicted the use of marijuana. In the case of the boys, there was only a moderate effect on their relationship with their friends. Reed et al. (2017) found that, among 793 American secondary school students, the girls reported more negative emotional reactions and disturbances due to dating violence exerted via electronic means, in comparison to boys.

Likewise, Haynie et al. (2013) concluded that the probability of reporting symptoms of depression, psychological complaints and use of alcohol was higher among adolescent victims of dating violence, compared to those who were not the object of this type of violence. The sample was a representative one, comprised of 2203 American students of tenth grade. The boys who were victimized reported more symptoms of depression and psychological complaints whereas the girls who were victimized showed more physical complaints and alcohol consumption. However, the girls who were victims of physical and verbal violence reported more symptoms of depression, somatic, physical and psychological complaints and greater use of alcohol and marijuana than the girls who only received verbal violence, results which suggest that the negative consequences are greater when more types of violence were suffered.

In Colombia, only one study has been carried out and published on the difficulties resulting from dating violence (Moreno-Méndez, Rozo-Sánchez, Perdomo-Escobar & Avendaño-Prieto, 2019; Rozo-Sánchez, Moreno-Méndez, Perdomo-Escobar & Avendaño-Prieto, 2019), despite the fact that there is evidence that indicates that this problem affects a significant number of Colombian adolescents and young adults. Thus, in a sample of 403 university students of the intermediate-sized city of Tunja, 82.6% of the participants reported having been the object of at least one type of dating violence on at least one occasion (Rey, 2009). At the same time, Martínez, Vargas and Novoa (2016) found in a sample of 589 secondary school students from the same city that 70.9% had been the object of at least one violent act, on at least one occasion. Redondo, Luzardo, García and Inglés (2017), for their part, reported that out of 237 university students from the city of Bucaramanga, 91.9% of the participants had suffered from verbal abuse. Through the methodology of structural equations, Moreno-Méndez et al. (2019) and Rozo-Sánchez et al. (2019) found in a sample of 599 Colombian students aged 13 to 19 that alcohol consumption, psychopathological symptoms, school maladjustment and emotional symptoms were associated with victimization among girls, and those same variables were related to the perpetration of dating violence among boys. Notwithstanding, this study did not directly examine the existence of differences by sex, as regards mental health and other issues among the participants who were victimized.

Due to the above, this study had the objective of examining if there were differences between sexes with respect to a number of psychopathological variables and other difficulties among adolescents who were victims of dating violence, taking into account some of the variables evidenced in the reviews conducted by Gracia-Leiva et al. (2019) and Rubfo-Garay et al. (2015) and the other studies previously cited. Said variables include psychopathological symptoms, clinical, personal and academic adjustments, substance abuse, suicide attempts and relationships with peers and relatives.

The participants were 757 adolescents between 12 and 19 years of age, 447 girls (59%) and 310 boys (41%), in grades seven to eleven from 15 secondary schools from Tunja (n=401) and Yopal (n=410), two cities in Colombia, who live in socioeconomic sectors low-low (n=106, 14%), low (n=305, 40.3%), medium-low (n=253, 33.4%), medium (n=60, 7.9%), medium-high (n=30, 4.0%) and high (n=3, 0.4%), according to the classification of the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE). The participants reported having had an average of 4.3 relationships. A total of 85.9% stated that they were heterosexual, 2.1% considered themselves to be homosexual and 4.2% bisexual. The parents of 34.7% of the participants are married, while 34% of their parents are divorced or separated, 3.2% are widows/widowers and 4.5% come from a single-parent family.

The criteria of inclusion and exclusion were the following: (a) having had at least one romantic relationship of at least one month; (b) being between 12 and 19 years old, the age range within which adolescence lies, according to the World Health Organization (2017); (c) being single; and (d) having the consent of both the parents and the students (except for those over 18). The selection of the students was carried out through a non-random sampling, according to their availability in the participating educational institutions. These adolescents were part of a bigger sample, made up of 811 individuals who took part in both prevalence studies conducted in the two cities mentioned.

Instruments

Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory, Spanish version (CADRI, Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006). This instrument was designed for adolescents and allows them to report the perpetration of acts of physical, verbal-emotional, relational and sexual violence, and threats to an intimate partner in the last 12 months, as well as those received from the other member of the couple in that same time period, through 25 pairs of items which respond to the Likert scale with the following possible options: Never (o), Hardly ever (1), Sometimes (2), and Often (3). It also includes another 20 items which provide an adequate solution to relationship conflicts which were not taken into consideration in this investigation in order to reduce the time of the application of the instruments.

The authors of the Spanish version of CADRI (Fernández-Fuertes et al., 2006) reported a structure of six components which explained 55.1% of the variance in the items of aggressions suffered. With respect to reliability, they found alphas that ranged from .51 and .79, with α=.86 for all the items of this part of the instrument. In the base sample of this research, the alpha values oscillated from .39 for the scale of threats made by the participant and .83 for the scale of verbal-emotional abuse carried out by the partner, with a general index of .87 for the aggressions exerted and .88 for the aggressions received.

Self-report questionnaire of psychological variables (Rey, 2012). It was developed in order to obtain information from adolescents about the consumption of alcohol and other psychoactive substances, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, and history of physical and sexual abuse, through 49 items with different response options. So as to obtain information about alcohol consumption and other psychoactive substances, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, various items of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [YRBSS] (Brener et al., 2004) were included and adapted, while for the items referring to the history of physical and sexual abuse, the family violence history tests developed by Renner and Slack (2006) were used. The instrument was reviewed on a methodological and content level by experts and tested on a sample of male and female adolescents.

Symptom Checklist-90-R, Spanish version (González de Rivera et al., 1988). It is a pen and paper questionnaire, which helps to identify the presence of 90 psychopathological symptoms related to the previous few weeks before the questionnaire was answered, using a Likert scale with the following possible options: None at all (o), A little (1), Moderately (2), Quite and Much or Extremely (3). In addition, the instrument presents the following scales: Somatization, Obsessions, Interpersonal sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic anxiety, Paranoid ideation and Psychoticism, apart from three global indexes of psychopathology: index of total severity, index of positive discomfort and a total of positive symptoms. The authors of the Spanish version found a structure of eight factors which explained 32.46% of the variance, between 570 Spanish men and women between 18 and 74 years of age, factors which they considered to be comparable to those of the original version. In the base sample of this research the alpha values ranged from .73 for the scale of phobic anxiety and .91 for the scale of depression, with a .98 index for all the items.

Behavior Assessment System for Children asnd Adolescents -self-report Spanish version- (BASC-S3; González, Fernández, Pérez & Santamaría, 2004). It is a multi-method evaluation system which allows for the assessment of children and adolescents through their parents and teachers' reports, a system of observation and a self-report version which is used as from eight years of age. The self-report version was used in this research, which includes the following scales: (a) Scales of school maladjustment: negative attitude towards school and negative attitude towards teachers; (b) Scales of clinical maladjustment: sensation seeking, atypicality, locus of control, somatization, social stress, anxiety, depression and sense of inadequacy, and (c) Scales of personal adjustment: self-esteem, self-confidence, interpersonal relationships and relationship with the parents. It includes an index of school maladjustment, clinical maladjustment, personal adjustment and an index of emotional symptoms. The reliability of the scales, reported by the Spanish researchers, is between .70 and .80, significantly correlating with similar measurements. In the base sample of this research, the alpha values oscillated between .047 for the self-esteem scale and .91 for the scale of clinical maladjustment, with a .91 global index.

Procedure

Authorization was requested for the selection of the participants in the educational institutions mentioned. Afterwards, the students were contacted and, in their classrooms, the objective, inclusion criteria, procedure and ethical considerations of the study were explained to them. The students who were interested in taking part in the study and who met the inclusion criteria were given an informed consent form in order to sign it with their parents. It contained the same information given to the adolescents in the first place. The instruments were applied collectively to those students who returned the form duly signed by them and their parents.

The gathering of information regarding the variables that would be associated with perpetration was carried out through the use of the Self-report Questionnaire of Psychological Variables (Rey, 2012), SCL-90-R (González de Rivera et al., 1988) and BASC-S3 (González et al., 2014). The data obtained was incorporated into an SPSS database version 22.o, amducting comparisons through the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and the size of the non-parametric effect, given that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test showed that the variables were not distributed normally in the sample of participants, thus, considering the size of the effect, under .3 small, under .5 moderate and equal to or higher than .5 high (Cohen, I988).

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethical committee for scientific research of the sponsoring institution to which the authors of this study are subscribed. In agreement with Resolution o08430 of 1993, Law 1090 of 2006 and Doctrine 3 of 2012 of the National Deontological and Bioethical Tribunal of Psychology, the adolescents were asked for their approval and their parents had to sign an informed consent form in order for their children to participate in this investigation. Said document contained information referring to the objectives and methodology of the study, the voluntary nature of the students' participation, the anonymous answering of the instruments, the confidentiality of the data obtained, the independence of the study with regard to the institution and the acceptance of the decision to withdraw throughout the investigation without incurring in any legal or social consequences. It was also guaranteed that their personal information would not appear in any report, presentation or academic publication of the study and that the information collected would only be used for research and academic purposes, in fulfillment of the previously mentioned norms. Based on Resolution o08430 of 1993, it was considered that the risk of the investigation was minimal. In addition, the information of the participants was not shared with any other people other than the members of the research group, in agreement with Law 15810f 2012, on personal data protection.

Results

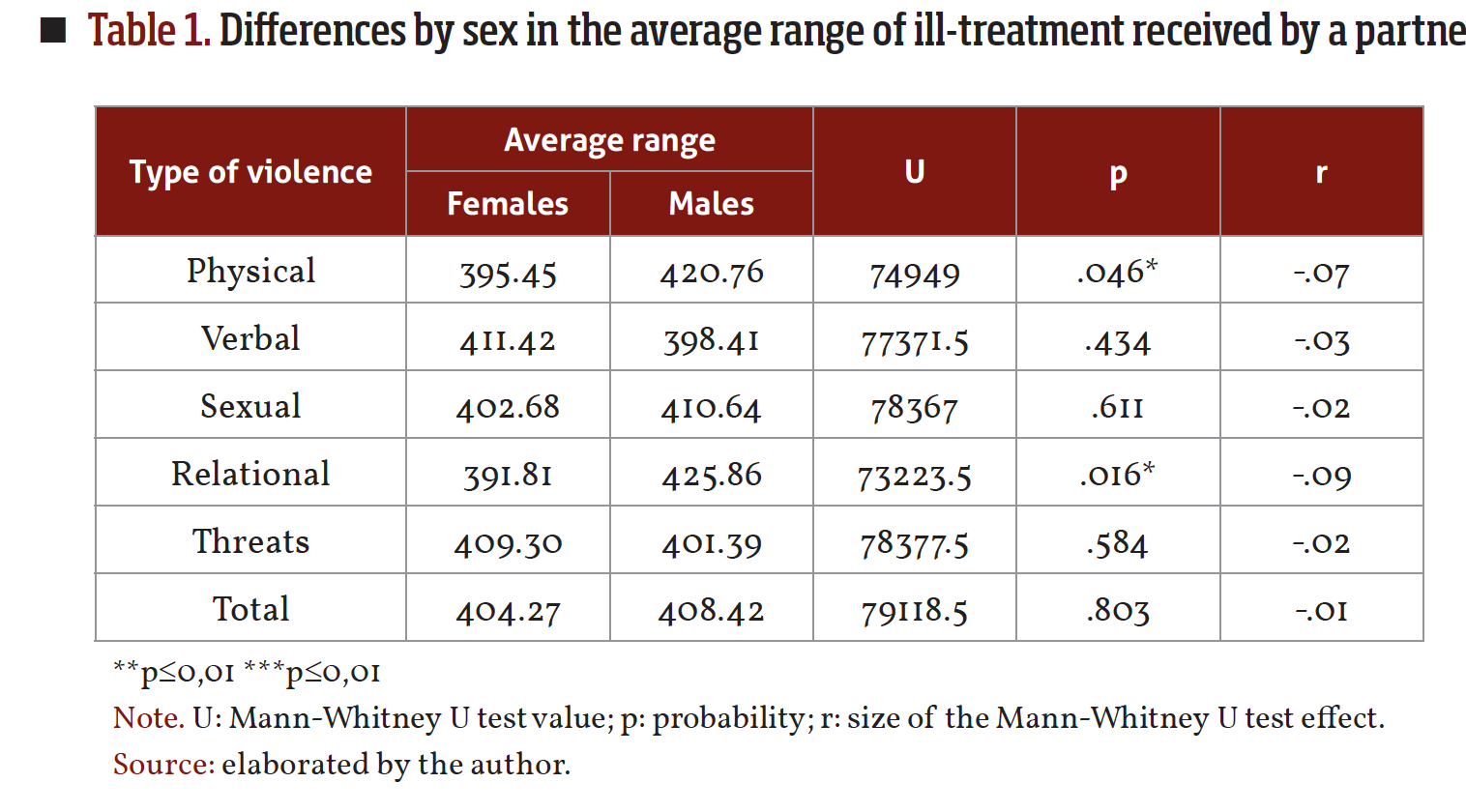

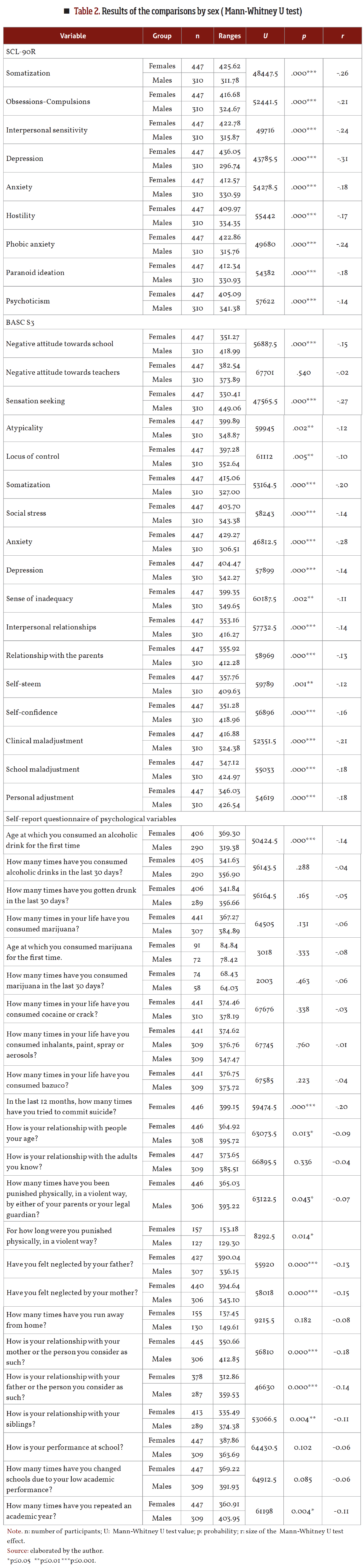

As can be seen in Table I, the boys reported having received relational and physical ill-treatment more frequently, although the effect is smaller. However, the girls showed score ranges that were significantly higher in all the scales of SCL-90-R (González de Rivera et al., 1988): somatization; obsessions-compulsions; interpersonal sensitivity; depression; anxiety; hostility; phobic anxiety; paranoid ideation and psychoticism, and the scales of BASC-S3 (González et al., 2004): atypicality; locus of control; somatization; social stress; anxiety; depression; sense of inadequacy, and clinical maladjustment, although with smaller effects.

Among the boys, significantly higher score ranges were found, compared to the girls', in the BASC-S3 (González et al., 2004) scales and indexes: negative attitude towards school, sensation seeking, interpersonal relationships, relationship with the parents, self-esteem, self-confidence, school maladjustment and personal adjustment, although with smaller effects (see Table 2).

Finally, in the Self-report Questionnaire of Psychological Variables (Rey, 2012), the boys reported a younger age of starting to consume alcoholic drinks while the girls reported a higher number of suicide attempts in the previous I2 months, compared to boys. They also reported better relationships with people their own age, as well as with their parents and siblings. Girls reported having been punished physically in a violent manner a higher number of times and for a longer period than boys, feeling more unprotected by their parents than boys. The boys have also claimed to have repeated more school years than the girls. Nevertheless, the scale of the effect was smaller regarding these differences (see Table 2).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine if there existed differences between the sexes with respect to a set of psychopathological variables and other difficulties, among adolescents who are victims of dating violence. The results show a series of differences that will be classified below.

At a psychopathological level, the girls evidenced significantly higher scores in all the scales of the SCL-90-R (González de Rivera et al., 1988) and in the scales of clinical maladjustment of the BASC-S3 (González et al. , 2004), obtaining a higher score in said index. In addition, the girls reported a significantly higher rate of suicide attempts in the last 12 months. The boys, for their part, revealed that they started consuming alcoholic drinks at a younger age, but the amount of alcohol consumed, as well as of psychoactive substances, did not differ from that of the girls. These results are in agreement with those of investigations that indicate a greater emotional impact and internalizing symptoms among women who are victims of dating violence (e. g., Foshee et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2017).

At a personal and family level, the girls also presented lower scores in the scales of self-esteem, self-confidence, interpersonal relationships and relationships with parents of the BASC-S3 (González et al. , 2004), showing even lower scores in the index of personal adjustment of said instrument and the questions related with their relationship with their peers, parents and siblings from the Self-report Questfonnaire of Psychological Variables (Rey, 2012). Moreover, in this instrument it was found that they received more violent physical punishment from their parents or caregivers, feeling less protected by their father and mother. The boys' scores were considerably higher in the sensation seeking scale of the BASC-S3 (González et al., 2004).

Finally, academically speaking, the boys scored higher with regard to their negative attitude towards school in the previously mentioned instrument, obtaining significantly higher scores in the school maladjustment scale, reporting a higher rate of repetition of academic years.

These results, as a whole, demonstrate that dating violence would not only affect girls more but, as has become evident in prevfous studies (Foshee et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2017; Reed et al., 2017; Rubio-Garay et al., 2015), it would impact boys and girls differently, causing a greater number of psychopathological symptoms in girls, affecting their personal, social and family lives, while in boys the impact is less, particularly in the academic area. Nevertheless, the comparative transversal nature of this research does not confirm if these difficulties were a cause or a consequence of dating violence, as is evident in variables such as the starting age of alcohol consumption, for this could be a trigger of the ill treatment, and in the sensation seeking scale of the BASC-S3 (González et al. , 2004), a personality trait that could have favored victimization, but not be a consequence of it. At the same time, the small size of the effect obtained shows that sex could have an influence on these differences, but it would be insufficient to explain them.

On the other hand, it is worth highlighting that most of the difficulties evidenced by victimized girls, when compared to those of victimized boys, are related to symptoms of an internalizing nature, such as depression, anxiety and somatization, which is compatible with the notion that these types of difficulties are more common among women, in general (Alarcón & Bárrig, 2015; Carragher et al., 2016; Sluis et al., 2017). However, the boys did not frequently report difficulties in aspects like interpersonal relationships and the consumption of psychoactive substances, nor symptoms such as hostility, which are considered of an externalizing nature or more prevalent among males.

Although more studies are required on the differences by sex in the difficulties associated with dating violence, the results obtained show that in the campaigns of case identification, the presence of multiple difficulties at a psychopathological level should be considered, as well as a greater personal, family and social maladjustment among female adolescents who are victims of dating violence, so that they receive a prompt and efficient intervention, evaluating and intervening in these difficulties. Among the boys victimized, the evidence collected in this study shows that they have more problems in adapting to school, an aspect that is to be taken into account for the identification, evaluation and treatment of cases.

Among the strengths of this research can be mentioned: the number of participants, the collaboration of various middle school education institutions of the participating cities and the use of instruments which are, mostly, well-known, the information of which allowed the triangulation of the results obtained. However, these results are limited to a geographical area of Colombia and to the participation of adolescents who attend school. For this reason, it is recommended that similar studies be conducted in other regions of the country and with adolescents who do not attend school. In addition, the selection of the participants was not random and the self-reporting nature of the instruments used might lead to a certain bias associated with self-selection and social desirability, respectively.

In future investigations, it would also be convenient to examine the influence of age on these difficulties, comparing both victimized young adults with adolescents. It is also necessary to carry out more longitudinal studies in which there is a measurement of dating violence in the first stage of the study in order to determine its influence on the future appearance of difficulties.

References

Alarcón, D., & Bárrig, P. (2015). Conductas internalizantes y externalizantes en adolescentes. Liberabit, 21(2), 253-259. http://ojs3.revistaliberabit.com/index.php/Liberabit/article/view/269/144

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5a Ed.). Washington: Author.

Brener, N. D., Kann, L., Kinchen, S. A., et al. (2004, sept.). Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 53 (RR-12), 1-13. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5312a1.htm

Carragher, N. , Teesson, M. , Sunderland, M. , Newton, N. , Krueger, R. , Conrod, P. , & Slade, T. (2016). The structure of adolescent psychopathology: A symptom-level analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(5), 981-994. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002470

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2a Ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., Fuertes, A., & Pulido, R. F. (2006). Evaluación de la valencia en las relaciones de pareja de los adolescentes. Validación del Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) - versión española. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6(2), 339-358. http://www.aepc.es/ijchp/articulos_pdf/ijchp-181.pdf

González, J., Fernández, S., Pérez, E., & Santamaría, P. (2004). Sistema de Evaluación de la Conducta de Niños y Adolescentes. Madrid: TEA.

Gracia-Leiva, M., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubiltos-Landa, S., & Páez-Rovira, D. (2019). La violencia en el noviazgo (VN): una revisión de meta-análisis. Anales de Psicología, 35(2), 300-313. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5336-5407

Foshee, V. , McNaughton, H. , Gottfredson, N. , Chang, L. , & Ennett, S. (2013). A longitudinal examination of psychological, behavioral, academic, and relationship consequences of dating abuse victimization among a primarily rural sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 723-729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.016

Haynie, D., Farhat, T., Brooks-Russell, A., Wang, J., Barbieri, B., & Iannotti, R. (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U.S. adolescents: prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal ofAdolescent Health (53), 194-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008

Hoefer, R., Black, B., & Ricard, M. (2015). The impact of state policy on teen dating violence prevalence. Journal of Adolescence, 44, 88-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.07.006

Johnson, R. M., LaValley, M., Schneider, K. E., Musci, R. J., Pettoruto, K., & Rothman E. F. (2017). Marijuana use and physical dating violence among adolescents and emerging adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 174, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.012

Ludin, S., Bottiani, J. H. ., Debnam, K., Solis, M. G. O., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2018). A cross-national comparison of risk factors for teen dating violence in Mexico and the United States. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 47(3), 547-559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0701-9

Martínez, J. A., Vargas, R., & Novoa, M. (2016). Relación entre la violencia en el noviazgo y observación de modelos parentales de maltrato. Psychologia: Avances de la Disciplina, 10(1), 101-112. https://revistas.usb.edu.co/index.php/Psychologia/article/view/2470/2165

Mercy, J. A. , & Tharp, A. T. (2015). Adolescent dating violence in context. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 441-444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.028

Moreno-Méndez, J. H. , Rozo-Sánchez, M. M. , Perdomo-Escobar, S. J. , & Avendaño-Prieto, B. L. (2019). Victimización y perpetración de la violencia de pareja adolescente: Un modelo predictivo. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 36, eI80I46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275201936e180146

Niolon, P. H., Vivolo-Kantor, A., Latzman, N. E., Valle, L. A., Burton, T., Kuoh, H., Taylor, B. , & Tharp, A. T. (2015). Prevalence of teen dating violence and co-occurring risk factors among middle school youth in high risk urban communities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, S5-S13. https://doi.org/10.10i6/j.jado-health.2014.07.019

Organización Mundial de la Salud (2017). Desarrollo en la adolescencia. Recuperado de: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/dev/es/

Peterson, K. , Sharps, P. , Banyard, V. , Powers, R. A. , Kaukinen, C. , Gross, D. , Decker, M. R., Baatz, C., & Campbell, J. (2018). An evaluation of two dating violence pre-vention programs on a college campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(23), 3630-3655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516636069

Redondo, J. , Luzardo, M. , García, K. L. , & Inglés, C. J. (2017). Malos tratos durante el noviazgo en jóvenes universitarios: diferencias de sexo. I+ D Revista de Investigaciones, 9(1), 59-69. https://www.udi.edu.co/revistainvestigaciones/index.php/ID/article/view/115/126

Reed, L. A. , Tolman, R. M. , & Ward, L. M. (2017). Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 59, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.05.015

Renner, L. M., & Slack, K. S. (2006). Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Understanding intra- and intergenerational connections. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30 (6), 599-617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005

Rey, C. A. (2009). Maltrato de tipo físico, psicológico, emocional, sexual y económico en el noviazgo: Un estudio exploratorio. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 12(2), 27-36. https://actacolombianapsicologia.ucatolica.edu.co/article/view/275/282

Rey, C. A. (2012). Estudio descriptivo comparativo de adolescentes varonesy adolescentes mujeres que presentan trastorno disocial de inicio infantily trastorno disocial de inicio adolescente. Informe de investigación, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Cotombia, Tunja. http://desnet.uptc.edu.co/DocSGI/AV582-6-0.PDF

Rey, C. A. (2013). Prevalencia y tipos de maltrato en el noviazgo en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes. Terapia Psicológica, 31(2), 143-154. https://teps.cl/index.php/teps/article/view/31/33

Rozo-Sánchez, M. M. , Moreno-Méndez, J. H. , Perdomo-Escobar, S. J. , & Avendaño-Prieto, B. L. (2019). Modelo de violencia en relaciones de pareja en adolescentes cotombianos. Suma Psicológica, 26(1), 55-63 http://dx.doi.org/10.14349/sumapsi.2019.v26.n1.7

Rubio-Garay, F. , Carrasco, M. A. , Amor, P. J. , & López-González, M. A. (2015). Factores asociados a la violencia en el noviazgo entre adolescentes: una revisión crítica. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 25(1), 47-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apj.2015.01.001

Rubio-Garay, F., López-González, M. A., Carrasco, M. A., & Amor, P. J. (2017). Prevalencia de la vfolencia en el noviazgo: Una revisión sistemática. Papeles del Psicólogo, 38(2), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2831

Sánchez-Jiménez, V., Muñoz-Fernández, N., & Ortega-Rivera, J. (2018) Efficacy evaluation of "Date Adolescence": A dating vfolence preventfon program in Spain. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0205802. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205802

Sluis, S. , Polderman, T. J. C. , Neale, M. C. , Verhulst, F. C. , Posthuma, D. , & Dieleman, G. C. (2017). Sex differences and gender-invariance of mother-reported childhood problem behavior. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 26(3), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1498

Wilson, K. L., Szucs, L. E., Shipley, M., Fehr, S. K., McNeill, E. B., & Wiley, D. C. (2019). Identifying the inclusion of Natfonal Sexuality Educatfon Standards utilizing a systematic analysis of teen dating vfolence preventfon curriculum. Journal of School Health, 89(2),106-114. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12718

Wincentak, K. , Connolly, J. , & Card, N. (2017). Teen dating violence: A meta-analytic review of prevalence rates. Psychology of Violence, 7(2), 224-241. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040194